“Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, the evidence will show that…”

Many a trial attorney has opened a trial by addressing the jury with words to this effect. But what exactly will the evidence show? The answer to that question depends not just on the facts of the case, but on the exact evidence that is likely to be admitted at trial. This means a trial attorney must understand the rules of evidence.

Evidence rules in legal proceedings will determine which evidence is admissible or inadmissible. Since the lawyer can only make arguments based on the evidence the judge or jury has seen and considered, it is critical they know the standards for objecting to evidence and how to steer the judge toward favorable evidentiary rulings.

Here, we have compiled a rules of evidence “cheat sheet” summarizing some common evidentiary objections in legal proceedings. While you must always carefully research the rules of evidence in your jurisdiction, this cheat sheet outlines some broad considerations for evidence at trial.

Admissibility of evidence: a brief summary

There are various forms of evidence that are admissible in court. The primary form we associate with trials is testimonial evidence, where a witness takes the stand and provides sworn testimony in response to attorney questions. Documentary evidence can also be admitted in the form of writings, records, blueprints, photographs, and various other document types. Tangible physical evidence, such as weapons or narcotics, can also be admitted as real evidence.

The primary test for the admissibility of any item of evidence is whether or not the evidence is relevant. As will be explained in more detail below, evidence is only relevant if it helps prove or disprove any fact important to the case. Beyond that preliminary consideration, there are several other potential objections to evidence being admitted, some of which are outlined in the cheat sheet below.

The court has discretion to make its own determinations on evidentiary rulings within some guidelines. This means a trial attorney must not only know the rules of evidence well, they must be able to argue them effectively as applicable to the present circumstances.

Rules of evidence cheat sheet: common objections

What follows is a cheat sheet for some of the most common objections you will make at trial or in pre-trial proceedings. Full disclaimer: this cheat sheet is not meant to be comprehensive and should not be relied upon as the final standard for an evidentiary issue in your case. Be sure to research the rules of evidence thoroughly in your jurisdiction before proceeding to trial or dealing with any evidentiary issues.

Relevance

Evidence must be relevant in order to be admissible. Evidence is considered relevant if it has any tendency to make a fact more or less probable, where that fact is consequential to the determination of the action.

Example

- Opposing counsel: “Did you inform your business partners of your drug conviction as a teenager?”

- You: “Objection, Your Honor. That question is not relevant to the matters at issue in this case.”

You should note that an evidentiary ruling on an issue such as this–a witness’s prior criminal conviction–will often be made prior to trial or otherwise in a hearing where the jury is not present. In fact, many pre-trial evidentiary rulings are made when the parties anticipate conflicts on evidentiary issues and bring them to the court’s attention.

Hearsay evidence

Hearsay is an out-of-court statement offered to prove the truth of the matter asserted. Since the person being quoted is not present in court, the jury cannot observe their demeanor and the opposing counsel does not have the opportunity to cross-examine them. This is why hearsay is generally deemed inadmissible.

Nonetheless, there are many exceptions to the hearsay rule, including the following:

- Excited utterance: Applies to someone making a statement during or immediately after a startling event, on the basis that such a statement is more likely to be unguarded and truthful.

- Statement against interest: A statement that would adversely impact the person making it, based on the assumption that such a statement is less likely to be fabricated.

- Matter of record: This exception allows for admission of government records, business records, and other documents where their contents are verifiably authentic, even though they are technically out-of-court statements.

- State of mind: If the speaker is describing their own state of mind, this exception is granted because there is little other evidence to determine this fact.

There are likely to be various other hearsay exceptions for your jurisdiction, such as prior inconsistent statements or statements of a party opponent. Be sure to research the hearsay rule and applicable exceptions for your case and jurisdiction.

Example

- Opposing counsel: “Did the crossing guard tell you she saw Mr. Smith run the red light?”

- You: “Objection. Calls for hearsay.”

Illegally obtained evidence

In criminal law cases, the government can be prevented from presenting evidence obtained by police or other government officials in violation of the U.S. Constitution. This is commonly invoked on the basis of the 4th Amendment’s prohibition against unreasonable searches and seizures. The government could also obtain evidence in violation of the 6th Amendment’s right to counsel for a criminal defendant. Under the exclusionary rule, the court must suppress illegally obtained evidence, and convictions based on such evidence can be reversed.

These evidentiary objections are generally resolved prior to trial. In fact, these evidentiary rulings often determine whether a criminal case goes forward at all. If a key piece of evidence (a wiretapped conversation or a coerced confession, for example) is suppressed under the exclusionary rule, the government may choose to dismiss the case.

Example

In a government prosecution for a drug-selling operation, the government may rely on a wiretap recording of a conversation between two defendants. If the wiretap was recorded without a search warrant, the defendant’s attorney could seek to have the recording suppressed, thus weakening the case–perhaps even resulting in a dismissal.

Probative value vs. prejudicial effect

Some evidence may have some probative value for a fact important to the case, but that probative value may be outweighed by the potential negative effects, such as: (1) unfair prejudice, (2) confusion of the issues, (3) misleading the jury, or (4) undue delay, wasting time, or needless presentation of cumulative evidence. (FRE Rule 403) The court has the discretion to apply a balancing test and potentially exclude the evidence.

Example

In a breach of contract action between two former business partners, one of the parties may prevail on a pre-trial motion to exclude evidence of that party’s time served in prison for an unrelated crime, on the grounds that this evidence has an unfair prejudicial effect outweighing its probative value. This is an example of how a cross-examination might proceed where the opposing counsel brings up the prison time despite the court’s order.

- Opposing counsel: “And were you unavailable at the time because you were in prison?”

- You: “Objection, Your Honor. May we have a sidebar.”

Note that you are not likely to actually name the objection of “probative value v. unfair prejudice” because you do not want to highlight this damaging information to the jury. If opposing counsel defies the court’s pre-trial order on an evidentiary issue, the court may go so far as to grant a mistrial.

Privileged evidence

Privileged information pertains to subject matter that cannot be disclosed or inquired into in any way. The law of privilege generally applies to communications within relationships that are protected as a matter of public policy. Accordingly, there are privileges for attorney-client communications, doctor-patient communications, and spousal communications.

Example

- Opposing counsel: “What did your attorney tell you to do then?”

- You: “Objection, their conversation is protected by attorney-client privilege.”

Lacks foundation

Some evidence cannot be admitted without first establishing a “foundation”–some predicate facts that provide a basis for its admission. An objection for lack of foundation is made when these predicate fasts have not been established. Some common scenarios for a lack of foundation objection include:

- The party has not demonstrated the witness is qualified to testify on certain subject matters.

- The party has not established the authenticity of a document or photo they seek to introduce into evidence.

Example

- Opposing counsel: [examination of defendant’s business associate] “How would you describe the state of the defendant’s marriage at this time?”

- You: “Objection. Lacks foundation.”

For more on common objections, check out our Depositions Objections Cheat Sheet.

You may like these posts

Rules of evidence cheat sheet: final thoughts

Litigators must be familiar with the rules of evidence and evidentiary objections. Allow this guide to serve as a broad overview of the most common objections, while committing yourself to becoming an expert on the rules of evidence in your jurisdiction.

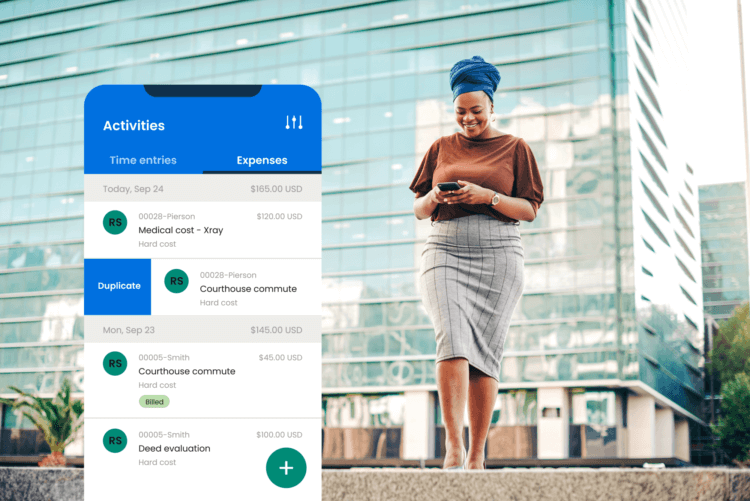

Modern trial lawyers can gain an advantage in this area with the right software to support their practice. Clio provides an assortment of solutions that support the overall practice and specifically trial practice, such as daily task lists and organization of evidence and testimony. Learn more about Clio for trial lawyers and consider booking a demo to delve deeper.

We published this blog post in April 2024. Last updated: .